One of my favorite classes in undergrad was a comparative literature course on the “Whodunit”. This would seem to be destined to be one of the examples cataloged by skeptics as to why university is waste of time, but it was in fact a wonderful introduction to Borges, Derrida and Eco. Besides the signs and semiotics, the course challenged us to read everything typologically and to see that the protagonists of the mystery genre are really all the same and rooted in a primordial literary archetype which we called “the problem solver”. Gregory House does not land far from Holmes, who does not land far from Oedipus.

A defining characteristic of “the problem solver” and what our instructor said in an impossible to mimic French accent was “convergence” – the detective usually has much in common with the perpetrator. There is an element of criminality in the “problem solver” which prevents him from identifying completely with authority, he is rather always triangulated between the law and the law-breaker. There is an essential element of danger.

There is this same “convergence” and dynamic of danger in the relationship between matzah and chametz. The constituents of matzah are deceptively simple consisting of flour and water. (Though as we shall see among the main challenges to making matzah by hand are determining what flour and what water are eligible.) The first question is what sort of grain we may use. The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chayim 453) lists the types of grain suitable for matzah:

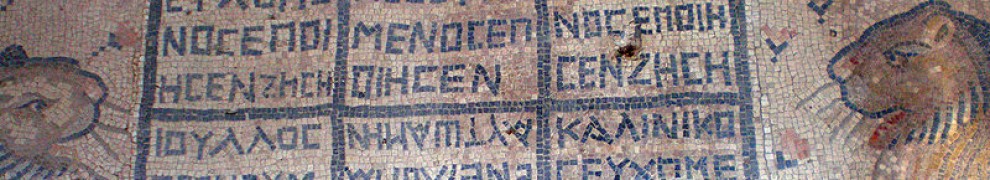

אלו דברים שיוצאים בהם ידי חובת מצה, בחטים ובשעורים ובכסמין ובשבלת שועל ובשפון אבל לא בארז ושאר מיני קטניות, וגם אינם באים לידי חמוץ ומותר לעשות מהם תבשיל

These are things with which one fulfills the obligation of matzah: wheat, barley, spelt, rye, and oats. But not with rice or other kitniyot, these do not become chametz and one may make other dishes with them.

The first thing to note is that although matzah can be made from any of the five grains listed, in practice we only make matzah from wheat. This is because wheat has a hard shell and is considered to be more resistant to water that may fall on it when we don’t want it to.

The second thing is that those who are used to the Ashkenazi traditions proscribing kitniyot may be taken aback at the Shulchan Aruch’s comfort with the use of rice and legumes during Pesach. And indeed Shulchan Aruch reflects Sephardi perspectives which (following rabbinic tradition) don’t have some of the strictures which evolved in northern Europe. But if one assumes that rice is permitted on Pesach, why can’t we use it to make matzah?

The rule is that nothing that can’t become chametz may be used to make matzah. The ingredients of matzah and chametz are identical – what makes a matzah a matzah is the care taken to bake the mixture of flour and water before it ferments and becomes chametz. This convergence between matzah and chametz is a requirement – and therefore if our understanding is that rice cannot become chametz no matter how careless we are then it can never grow up to be a matzah. No danger, no matzah. (This is one of the reasons that some packages of egg matzah say “not for use on Passover”. Flour and egg have no chance to become chametz as long as one is very careful to avoid contact with water.)

This aspect of danger is why when you begin talking about making your own matzah for Passover, friends and concerned non-friends start to back away. This can’t be taken as a wholly unreasonable reaction. When everything has been kashered and cleaned, a bowl of flour and a cup of water are the ingredients for a bomb. It isn’t just easier so much as it is quite a bit safer to farm out the making of matzah to experts who can be counted on to defuse a sticky situation. And while I was given some encouragement when I starting several months ago to prepare ( by studying the laws of matzah and gathering what resources there are on how to make kosher for Passover matzah by hand), mostly people told me not to do it. Their advice was well-intentioned and pretty sensible given some of the obstacles.

But as I studied, the project became less a quest for better tasting matzah (though I still hope that the matzah tastes good) but a mission about what Judaism is about: We should be able to do difficult, even dangerous things as adults. Our parents took this for granted. Torah is the same way. There are different ideas about who is worthy to study Torah, but I don’t think any school holds that there is any Torah without danger, and that when used inappropriately Torah can do more harm than good. It is likened to medicine that when taken with care can bring great healing, but when used carelessly is a deadly poison. The care and discernment we have to bring. A full life is not without risk, and it is the care that is required to make the matzot – knowing that if we do it wrong we are in trouble – that brings elevation to the bread which is the foundation of the festival. We should not farm this out.

I’m a bit behind on where I hoped to be blogging-wise, so this not going to be the “how we will make matzah” blog I set out to do but more of a “how we made matzah” blog. I still have a lot to write, next I hope to cover the preparation of flour for matzah.